There are Muslim men fighting for the right to kill their wives. Groups of hard-line, right-wing Islamic extremists across Pakistan have banded together in protest to reclaim the right to abuse and kill their wives and daughters.

The country has finally taken a progressive step forward on gender equality, but some men still believe the mistreatment of women is their divine, God-given right. The controversy began when the Pakistani government introduced the Protection of Women Against Violence Bill, which effectively criminalizes violence against women in Punjab — the country’s most populous region.

Before the law was officially enacted on March 1, diehard extremists attempted to block the legislation, saying it would “destroy the family system in Pakistan” and “add to the miseries of women.” The bill was passed unanimously by the Punjab Assembly, and opponents have since warned of ongoing protests if it is not repealed.

What is the bill?

The Protection of Women Against Violence Bill criminalizes any and every form of abuse by men against women, whether it be domestic, emotional, psychological or done through stalking and cybercrime. It provides for a network of shelters or safe houses where women who have fled violence can seek counseling and financial and medical aid.

It also conceives a universal, toll-free, 24/7 telephone number women can call in order to report abuse. In special circumstances, offenders may be monitored by wearing a bracelet with a GPS monitor, and will be restricted from making gun purchases.

The bill was drawn up in 2015 by the political party of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. It was a surprise to many in the population, as the party has gained a reputation for pandering to right-wing religious groups. In recent months, however, Sharif has publicly condemned violence against women and honor killings, and vowed to take action.

In February, he told The Guardian: “This is totally against Islam and anyone who does this must be punished and punished very severely.”

Why is the bill important?

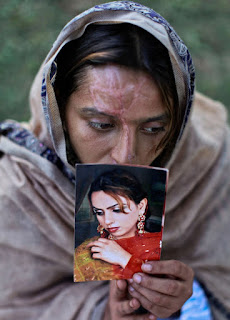

Violence against women is an endemic social issue in Pakistan. Wives and daughters are often still treated as domestic property. Honor killings, acid attacks, bride burnings, child marriages, and sexual and domestic abuse are commonplace, yet these crimes are grossly under-reported.

The United Nations’ Gender Inequality Index puts Pakistan 147th in a list of 188 countries. A 2014 report by the Aurat (Woman) Foundation, a women’s rights group based in Islamabad, said that every single day of the year, six women were murdered, six were kidnapped, four were raped and three committed suicide.

They also reported as many as 7,010 cases of violence against women in the province of Punjab. These figures do not include dowry-related violence and acid attacks, crimes which are also serious and frequent.

According to Pakistan’s independent Human Rights Commission, nearly 1,100 women were killed in Pakistan last year alone by relatives who claimed they had “dishonored” their families. In most of these cases, the victim is usually murdered by a close male family member.

Until this bill was enforced, women in the country were victims of a weak criminal justice system and an overall lack of social support, giving rise to horrific stories of honor killings, acid attacks and ongoing abuse.

These issues recently came to light in the Academy Award-winning documentary “A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness.” It followed the story of Saba Qaiser, a 19-year-old Pakistani girl who was beaten, shot in the head by her father and thrown into a river for marrying the man of her choice. Miraculously, she survived, and her story ended up receiving a heap of attention both in Pakistan and globally, soon prompting Sharif to promise a crackdown on honor killings.

In an interview with The Guardian, filmmaker Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy said the main problem with “honor” killings is that it’s considered to be a private matter — rather than a public legal issue. “People hush it up: A father kills a daughter, and nobody ever responds, nobody ever files a case. The victim remains nameless and faceless, and we never hear about them,” she said. “People feel, ‘If we register a case, it will bring shame to the family.’”

Who is opposing the bill?

Right-wing, extremist Islamic leaders spent copious amounts of energy trying to block the protection bill from being passed, and continue to oppose it. They’ve deemed the bill “un-Islamic,” contradictory to verses of the Koran, and an attempt to secularize, or Westernize, Pakistan.

In a press conference, one of the country’s own parliamentarians, Muhammad Khan Sherani, reportedly claimed the bill will actually have a detrimental impact on women and “traditional” family life. He claimed the protection act was “un-Islamic,” saying: “The law seems to have the objective of pushing women out of the home, and increase their problems.”

Maulan Fazlur Rehman, chief of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazl party, reportedly told local media the laws were “in conflict with the Holy Koran, the life of Muhammad, constitution of Pakistan and values of our country.”

“Husband and wife are considered partners in the West, but it is not the case in Pakistan,” he said. He called it a “Western conspiracy,” saying it represents “the blind following of American and European cultures.” He even went as far as to say it would break up homes, destroy the position of men in the home and invoke God’s wrath on the country.

A contributor for the New York Times, Mohammed Hanif, summarized their twisted logic as follows: “If you beat up a person on the street, it’s a criminal assault. If you bash someone in your bedroom, you’re protected by the sanctity of your home. If you kill a stranger, it’s murder. If you shoot your own sister, you’re defending your honor. “I’m sure the nice folks campaigning against the bill don’t want to beat up their wives or murder their sisters, but they are fighting for their fellow men’s right to do just that.”